When I was a child I tunneled through the public library like a shipworm.

Damon Knight, Creating Short Fiction, 155

Writers are often encouraged to read voraciously, but it isn’t just zeal that we are told to adopt: We are called to be omnivores. If a text is encountered along the road, we are not to question if we are hungry or whether we fancy the flavor, it us our duty to snatch it up in our jaws and guzzle it down, bones and all.

But even the Eaters of All shouldn’t just be mindless consumers, devouring every lick of text that comes in reach of our greedy jaws.

Consider Damon Knight’s advice on the subject:

What Should You Read? Everything. You should read Shakespeare and William Gibson and Dostoevsky, and you should read the labels on ketchup bottles, but you should read everything when you want to read it. If you approach any reading as drudgery, it will be drudgery. Try the classics from time to time, but if you find them boring or incomprehensible, put them down again. You may not be ready yet.

Damon Knight, Creating Short Fiction, 197

This Eat Everything but Never Drudgery approach is consistent with Knight’s advice in general. He is the master teacher of joyful observation, admonishing the writer to learn how to see, hear, taste, touch, and remember – even labels on ketchup bottles. (Indeed, he probably taught Ra’s al Ghul to Always Mind Your Surroundings.) Note also the assumption that the classics are deserving of being singled out – and that readers grow.

Or consider another adjacent piece of advice, this time from Michael Moorcock’s interview with The Guardian where he offers 10 rules for writers:

My first rule was given to me by T.H. White, author of The Sword in the Stone and other Arthurian fantasies and was: Read. Read everything you can lay hands on. I always advise people who want to write a fantasy or science fiction or romance to stop reading everything in those genres and start reading everything else from Bunyan to Byatt.

Michael Moorcock, “Michael Moorcock’s rules for writers,” The Guardian

So, read everything but don’t read in your genre if you’re writing fantasy, sci-fi, or romance (I bet he’d also include any of the other “genre” fictions under this umbrella-ban as well). Still, while I understand and agree with the admonition to read beyond one’s genre, you do eventually need to read it.

While this “read everything” kind of advice is helpful in so far as it liberates one to go read anything that comes in reach – with the implied assurance that such reading will benefit the would-be writer – its lack of direction can leave one floundering in the Waters of Possibilities.

But how should we navigate these waters, Dear Reader? Well, instead of laying out the theory and arguments of what and why and how to read, I’m going to sketch out my Read to Write Strategy with its accompanying rationale.

Let us begin with poetry.

Poetry as T’ai Chi Form

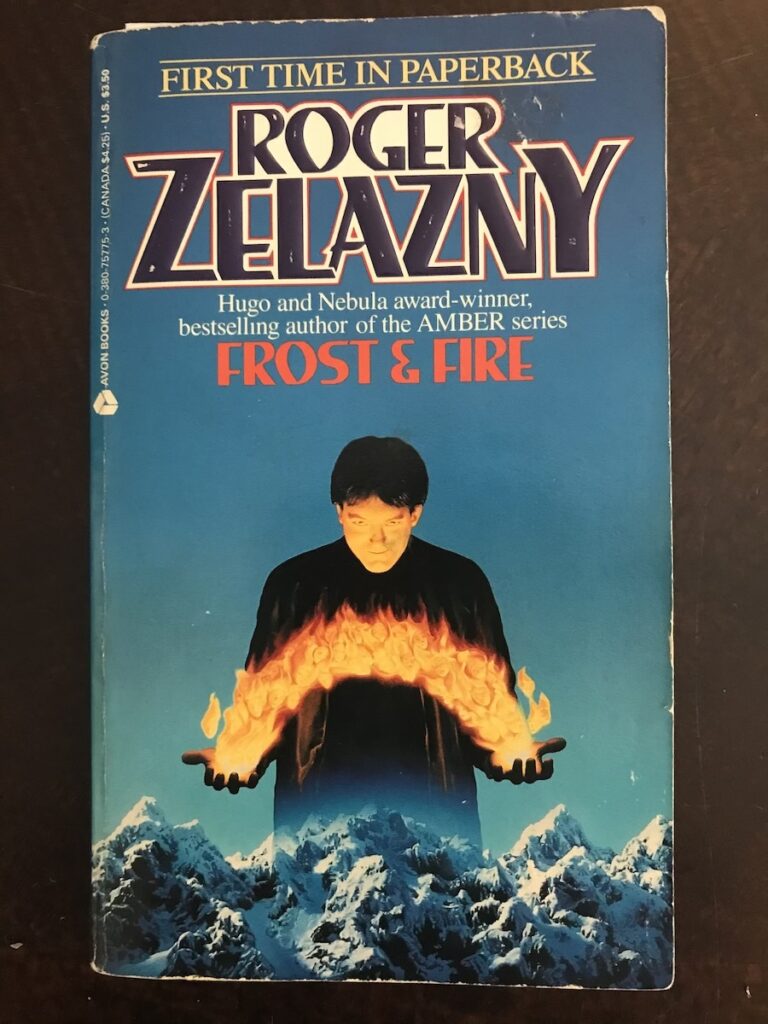

I read some poetry every day. It’s the closest thing I can think of for a prose writer in the way of exercising the writing faculties as something like a daily run through a t’ai chi form might the body.

Roger Zelazny, “An Exorcism of Sorts,” Frost & Fire, 12

Sometimes when you sit down to write, your mind just feels sluggish. In that moment, you can easily believe there is nothing artful in you, just plodding mundanity. How are you to conjure the fire when all your kindling feels soaked? How can you make beauty when your palette seems empty of color?

You can’t.

But do professional athletes just leap into action out of the grogginess of sleep or the daily routines of home life? No. They train, they exercise, they keep themselves limber and attuned – not just physically, but mentally.

That’s why I adopted the practice of reading poetry every day. There is a focused and distilled power in the best poetry, and if you read it consistently and thoughtfully, that power can be yours. (And poetry is such a joy to read!)

Like Zelazny, I personally prefer poets like W.S. Merwin, who provoke my imagination with their powerful evocation of imagery. Consider this excerpt from a poem that served as one of the inspirations for a short story of mine:

Watching the sea outside the broken

W.S. Merwin, “Deception Island,” The Drunk in the Furnace, lines 21-24

Temple of the cold fire-head, and wondering

Less at the wastes of silence and distance

Then at what all that lonely fire was for.

Zelazny is not alone in praising the value of reading poetry. In his 2010 Interview with the Paris Review, Ray Bradbury was asked by the interviewer where his famed lyricism came from. Here is his answer:

From reading so much poetry every day of my life. My favorite writers have been those who’ve said things well. I used to study Eudora Welty. She has the remarkable ability to give you atmosphere, character, and motion in a single line. In one line! You must study these things to be a good writer.

Here, Bradbury conflates excellent prose with poetry, but that’s because the best of prose approaches poetry. And that’s why his prose is never, ever boring. So, yes, I read poetry every day because I would like to approach something like Bradbury’s wondrous lyricism.

But, beyond reading poetry, Damon Knight actually encourages would be writers to write it (something that Bradbury did also):

If you are wise you will also write it—not free verse, at least to begin with, but rhymed, metric poems—sonnets, triolets, even limericks. Working within the constraints of formal verse will strengthen your grasp of prose.

Damon Knight, Creating Short Fiction, 160

I’ve written poetry off and on since 8th grade. And I certainly agree that the practice has helped my prose improve. In prose, there’s often the assumption that you can have a dull line or a boring phrase in longer works simply because you have to write so much. Poetry offers no such false mercy.

In addition to reading and writing poetry, I keep a Poetry Portfolio notebook where I copy down favorite poems and verses. I’ve shared briefly about this Portfolio, inspired by Robert Pinsky’s book Singing School, in my newsletter “Let Us Speak of Notebooks.” Whether it’s a speech by Prospero from The Tempest or my own (fumbling) translation of Borges “The Sea,” the notebook can hold the verse’s magic for me to return to later. And writing poetry down gets me thinking poetically, even if only for a little bit each week.

Well, we have touched on the value of poetry for Reading to Write. Let’s move on to the matter of scope.

Eat Deeply More Than Widely

Regardless of their quality, it is always better to read a few books carefully than skim through many, and, short of a personal taste which cannot be formed overnight, snobbery is as good a principle of limitation as any other.

W.H. Auden, “Making, Knowing and Judging,” The Dyers Hand, 40

Rather than just eat book after book, I take my time reading. Also, I’m selective about what I read. Thankfully, I’ve developed personal taste so I don’t have to rely on snobbery to limit my reading. But that doesn’t mean I only read the Great Books:

A poet who wishes to improve himself should certainly keep good company, but for his profit as well as his comfort the company should not be too far above his station. It is by no means clear that the poetry which influenced Shakespeare’s development most fruitfully was the greatest poetry with which he was acquainted.

Ibid, 37

According to this principle of Good and Comforting Company, I like to have something light on the menu, along with a classic. Still at this point, if I’m taking Auden seriously, who is above my station? Well, I won’t be trying to read Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake anytime soon – but that’s because the book is absurd.

But, jests aside, I do think there’s something to this “above his station” comment. I recently re-read Le Guin’s The Tombs of Atuan. This is the third time I’ve read it but it’s also the first time I gave it a close reading. Only now do I feel that I appreciate it – indeed, I actually teared up near the end. As Damon Knight said, sometimes you’re not ready to read something.

If I had been reading merely to consume the maximum amount of volume, then I could certainly have logged the pages read and cut a notch for another book read – but I would have risked not encountering the treasure within.

With considerations of scope established, I find this to be the opportune time to set down a personal element that fits into my reading mix.

The Bard and I

Shakespeare combines poetry with narrative and masterful characterization, and he is rightly considered by many to be the greatest author who ever lived. Now, you’ll occasionally find someone who says, “Shakespeare is overrated.” I obviously don’t hold with that camp, nor do I find its arguments credible.

When I was younger and had only read as much Shakespeare as was required to graduate High School, then certainly, I probably would have agreed. But the more time I spend reading and studying the Bard’s work, the more I am convinced that T.S. Eliot was at least partially right when he said:

Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third.

(I’ll leave you to guess what I think Eliot got wrong in his assertion – if you are so inclined.)

I keep one of the Bard’s plays in my active reading list at all times. After finishing reading through a number of the tragedies and the Tempest, I’ve recently been working through the English history plays: King John, Richard II, and – most recently – Henry IV Part I. (There’s no sense in my denying that I rather love Henry IV.)

Along the way, I am also reading from W.H. Auden’s Lectures on Shakespeare, though the lectures aren’t written according to the reading order I’m following. That said, consider this interesting comment of Auden’s from the opening lecture:

The first question to ask is what is the interest, the central kind of excitement inducing an author to write a work, as opposed to the wayside stimuli that may have amused him along the way. In the chronicle play, which is historical, not myth or fiction, the central interest is the search for cause and pattern, a depiction not merely of the event, but of the cause of it and its effect.

W.H. Auden, Lectures on Shakespeare, 3

Now, you have to be clear up front: You’re not reading Shakespeare for historical accuracy, even if you’re reading a “historical” play. What you’re getting in a Shakespearean history play is his insights into “cause and pattern” woven around the characters that he creates out of the alchemy of the historical record and his imagination. You’re getting at what interested him about the subject and how it inspired him to create his own work.

That’s part of why Shakespeare gets singled out for special attention in my Read to Write Strategy.

Reading Inside and Outside of Genre

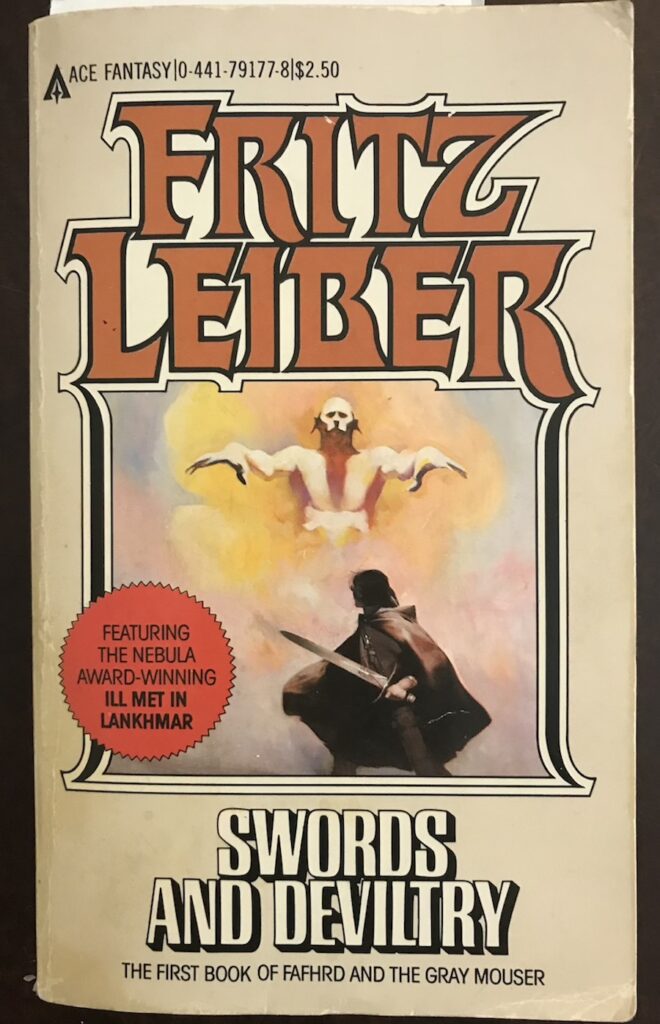

The other objects of my Read to Write Strategy are straightforward: I like to read something old (I just finished Beowulf again recently), something classic (I’m slowly working on Proust’s In Search of Lost Time), something by Gene Wolfe (I’ll finish re-reading Innocents Aboard sometime soon), and something that relates to what I’m inspired to write (right now I’m working through Swords Against Deviltry by Fritz Leiber and Three Kingdoms Volume 1).

Those aren’t the only books I’m reading now-a-days, but they’re the ones on my list. I might add in a book on history or literary theory or the writer’s craft, but I’m trying to always have something of the mix I’ve described above in circulation.

I’ve found it best to keep a variety in the mix not only in terms of subject matter but also in terms of form. You can read a poem a day with great ease (well, if other personal circumstances allow). Short stories can be read in one to two sittings. Sword and sorcery like Leiber requires less mental processing power than Proust. I read Beowulf in verse translation, so that was different than reading prose. Shakespeare is a quick read for me to just read for coverage, but I can linger if I like. And so on.

Unlike Wolfe, I don’t count a book like Marks’ Standard Handbook for Mechanical Engineers amongst the great influences on my writing, but I try to follow interests outside of the expected boundaries when whim strikes me. (Perhaps one day, I’ll get around to finishing Bringhurst’s The Elements of Typographic Style…)

With all that has been said thus far, we have come to something more of the how of my reading strategy.

Reading to Learn the Forbidden Arts

The best way to learn how this is done is to read fiction critically, asking yourself whenever you feel some response to the story, “How did she do that? Why did she do this?” Begin with stories of the kind that you ordinarily read for pleasure.

Damon Knight, Creating Short Fiction, 84

If you ‘re going to learn from other authors how to write well, it’s likely you’ll have to read in such a way that you actually lose some of the pleasure you take from their works.

This is because when you’re reading, you tend to allow the magic of the book to take over. You suspend your disbelief and enter a special state where the text is projecting its world for you. Now, when you stop yourself and look behind the curtain, you can discover the secret of the enchantment. But in so doing, the spell won’t work the same way when you go to read that favorite passage in the future.

The question you have to ask yourself is: Is it worth it? Is it worth it to know how to make such beautiful and powerful enchantments, if it’s going to take away the pleasure that you have reading the books that you love most? Personally, I don’t close read Gene Wolfe’s Solar Cycle books. I’ll put a little post-it inside when something really strikes me or I want to be able find certain passages again, but I don’t close read. That’s because I don’t want the pleasures of reading Wolfe’s greatest work to be diminished by looking too closely into the workings of his art.

That said I will close read The Brothers Karamazov or Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky, as I don’t have quite the same desire to protect myself from disenchantment with those masterworks.

Wolfe’s Best Advice for Aspiring Authors

Now, in addition to reading closely, there is a technique that Wolfe himself recommends in a very short essay found in The Best of Gene Wolfe, where he talks about what he considers his best advice for helping writers learn how to write. It’s an approach that’s been attributed to Benjamin Franklin but whoever is responsible for it, Wolfe is certain of one thing: It works.

Here is how he introduces the approach:

Every so often I get optimistic and explain the best method of learning to write to students. I don’t believe any of them has ever tried it, but I will explain it to you now.

(There, if that’s not throwing down a gauntlet, I don’t know what is!) Alright let’s hear the whole thing from Wolfe:

Find a very short story by a writer you admire. Read it over and over until you understand everything in it. Then read it over a lot more. Here’s the key part. You must do this. Put it away where you cannot get at it. You will have to find a way to do it that works for you. Mail the story to a friend and ask him to keep it for you, or whatever. I left the story I had studied in my desk on Friday. Having no weekend access to the building in which I worked, I could not get to it until Monday morning. When you cannot see it again, write it yourself. You know who the characters are. You know what happens. You write it. Make it as good as you can. Compare your story to the original, when you have access to the original again. Is your version longer? Shorter? Why? Read both versions out loud. There will be places where you had trouble. Now you can see how the author handled those problems.

The goal is to see more clearly how to write a really good story by imitating a masterwork. This is not so different from what painters do when they reproduce the works of great painters. But in Wolfe’s case, it’s done from memory and meditation, rather than by copying from reference.

Wolfe states that most of the writers that he’s taught this technique don’t seem to have ever put it to use. I plan to be an exception, but I have yet to pick one short story that I want to devote such entire focus and attention to. (Wolfe provides his own “The Boy Who Hooked the Sun” as an example work of the appropriate length. This story is the piece to which this little essay comes as an afterword. Obviously, Wolfe is confident that he is a master storyteller and this is a master story. And he’s right on both counts. Perhaps I will take him up on the offer…)

Becoming the Omnivore Who Reads to Write

Read what gives you delight – at least most of the time – and do so without shame.

Alan Jacobs, The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction, 23

So if we make a rough summary of my Read to Write approach, we end up with something like this:

- Eat Everything but Never Drudgery

- Exercise with Poetry Every Day (and write it occasionally too)

- Eat More Deeply Than Wide

- Find Good and Comforting Company (but keep making friends)

- You Can’t Go Wrong with the Bard

- Maintain a Varied Menu of Subject and Style (in and out of genre)

- Look Behind the Curtain

- Reproduce Master Works by Memory and Determination

So, there we have it, the menu that I have honed (can one hone a menu?) since the beginning of 2022. It shares similarities with other approaches that I have tried in the past but this is the first version of the idea that I have felt real confidence in.

And it has proven itself to me in the most persuasive way a model can: It has born good fruit.

Want more words? See the horse below about a newsletter. Or scroll on down to make a comment.