Ideas are the fundamental elements of stories, indeed they are the very kernels of worldbuilding. Where they come from, how to consistently generate them, issues of inspiration and influence, and how to weave your ideas in narrative unities are all topics for fruitful discussion. Yet the following essay isn’t primarily concerned with those concepts (though it will touch upon them as we go).

No, we’re going to delve into how ideas become stories. Specifically, we’re going to explore the methodology of creatively dialoguing with the elements you have.

If you want to start writing a story, then you need ideas. But you only need one idea to begin.

Let’s start our discussion with an illustration from tabletop roleplaying.

Inside Out and Outside In

There are many ways to build fictional worlds. If you are a talented linguist like J.R.R. Tolkien, you can start by creating new languages and then create a setting to make their home. If you are an artist, you can start with look and feel and then go from there. I am a historian by training, so that’s the lens I tend to look through.

Chris Pramas, “Inside Out and Outside In”

Chris Pramas is an award-winning game designer, writer, and publisher. His most famous publication credits include: the Dragon Age RPG, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay (second edition), and Freeport: The City of Adventure.

In The Kobold Guide to Worldbuilding, Chris wrote a brief essay on the creation of Freeport titled “Inside Out and Outside In.”

I’ve encountered the concept he lays out elsewhere, both in game design and fiction writing: big to small, small to big; macro to micro, micro to macro. But the language of inside out and outside in is catchier, more memorable, and more elegant.

Here’s how I like to think of the concept, using two related but contrasted movements:

- Inside Out: You have a starting point like a recurve bow, a character, or a city – and the story/world grows out from that point.

- Outside In: You have a starting frame like an intergalactic conflict, a world, or a continent – and you fill in the container.

(Yes, a city could be engaged outside in and a world could be a starting point for inside out, but let’s not get too tangled up with particulars – it’s about how you approach growing the idea.)

How did Chris grow a city?

The Inside Out Birth of Freeport

I knew I wanted to write a city adventure.

That’s the first idea Chris had for the beginning of Freeport. But he also gives his reasoning: it’s the kind of adventure that the gaming industry would be looking for with the launch of the new edition of D&D.

It can be easy to miss, but actually the launch of the new edition is the fundamental idea, the (implied) provoking question that started the whole process: What kind of adventure, Chris, are you going to write in response to the new industry initiative?

The next idea comes after the city idea:

I also knew I wanted a place where characters from all over might meet, so that argued for a port and it was a short hop from there to pirates.

The first idea (city) in a D&D style world, led to a second related idea (port) that dragged in a third (pirates) right behind it. This is an inside out movement of ideas, a single idea is growing outwards, taking on definition as it expands.

The process is one of accumulation.

At this point he brings in an atmospheric flavor, a metaphysical element even:

I thought much of the adventure should be an investigation, which made me think of Call of Cthulhu…It was a setting that combined classic D&D fantasy with Lovecraftian horror and pirates.

A theme of investigation is the fourth idea, but it quickly acquires a dimension of cosmic horror (instead of something more like Sherlock Holmes, Garret P.I., or Harry Dresden).

Notice how one idea leads to the next in a series of connections. Almost an If-Then model: If port, Then pirates; If investigation, Then Lovecraft.

Written up, the module Death In Freeport came to 32 pages. And it established Green Ronin Publishing as one of the teams to be watched in the new 3rd Edition D&D era.

The Outside In Expansion of Freeport

Chris only had a chapter to work with in The Pirate’s Guide to Freeport where he contributed to the broader world of Freeport, so he painted with a big brush:

The chapter delves into the history of the ancient serpentman empire, the cosmology of the setting (which uses Yig as a sort of world serpent), and gives an overview of “the Continent.”

These are big topics that give broader context and definition to the setting, but not a lot of detail. Instead, he provides substantial pillars to build the world around. He went on to sketch more frames on the Continent to be filled out by Gamemasters who bought the book:

I included entries for each nation like important landmarks. These were just names with no description provided, dangling mysteries for GMs to explore.

These are gestural sketches. Not so dissimilar from Obi-Wan mentioning the Clone Wars in A New Hope or Han bringing up Ord Mantell in The Empire Strikes Back. They give definition to the world, but they’re hollow at the time of their creation. Vessels waiting to be filled.

So, we can see that instead of a process of accumulating, the outside in approach is about creating frames for filling (and you don’t always have to fill them).

Getting At the Mechanics of the Method

The approach of Inside Out and Outside In is a way of dialoguing with your ideas. You pick an idea and a method you want to apply (accumulate or frame), and you start thinking. Then stuff happens: this idea leads to that idea, which leads to the third, fourth, and fifth in an organic manner that seems almost inevitable when he describes it.

But it’s important to remember that Chris Pramas has a lot of experience under his belt. He was a freelancer starting from 1993 and co-founded Green Ronin Publishing in 2000.

So even in talking about the topic, he’s not getting too deep into the gritty, implied mechanics of his process – because for him a lot of things have become second nature.

We practice mechanics so that we don’t have to think about them when we’re performing our art. Let’s take pitching in baseball:

Pitchers work on their release, stride, ball spin rate, their grip on the ball (four or two seam), their stance when there’s a runner on 1st (keeping the runner honest and avoiding a balk), even toeing the rubber.

And they don’t think about any of those things once they get out there and start pitching their game. Now, if they get thrown off their game and start to stink up the place, someone comes out to the mound and tries to help them identify the problem, but mostly it’s all letting the ball fly as the game is called.

So how might we think about the implied mechanics of what Chris is talking about? The answer is questions.

Dialoguing Your Ideas with Questions

I keep six honest serving-men (They taught me all I knew); Their names are What and Why and When And How and Where and Who. I send them over land and sea, I send them east and west; But after they have worked for me, I give them all a rest. "I Keep Six Honest Serving Men" (an excerpt) by Rudyard Kipling

Earlier in the discussion I mentioned the “provoking question” that set off the chain of thoughts that led to Freeport:

What kind of adventure, Chris, are you going to write in response to the new industry initiative?

We don’t know if anyone actually asked him this question, but his response to the opportunity before him is his answer. And his mind rose to the challenge, making creative decisions to craft a new setting.

Yet, there’s more than just the provoking question that’s implicit. There is a question that implicitly proceeds every decision he made.

Where are the players going to meet?

What flavor is the city going to have?

What is the theme of the setting?

Chris might not have asked himself these questions because he was already a veteran at his craft, and just had to show up to the plate and pitch his game. He had plenty of years of familiarity with D&D settings to draw upon.

But they are questions that are inherit to his craft, even if answering them has become instinct.

He knows the problems of game design: there has to be a place for the adventure to happen, there has to be a way to bring characters together, there should be elements that bring distinctiveness to the world, there should be something bigger behind the scenes, and – above all – it should be exciting both to create and consume.

And knowing the problems means he knows the questions to interrogate the seed of his inspiration. He has internalized them in his creative process.

Tent Pole Questions

Well, what if we’re not historians with a background in writing in our field like Chris? What if we have one good idea but don’t know the questions to ask to grow a world or a story?

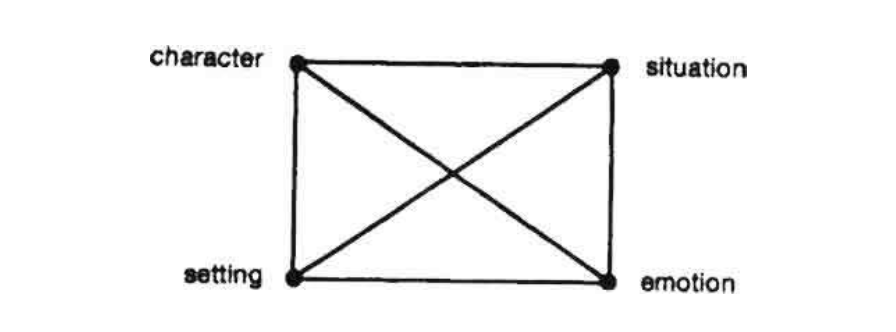

In his book, Creating Short Fiction, Damon Knight provides a simple model to get a story growing. He calls it the four tent poles:

You build the tent by bouncing from pole to pole, seeing what comes about from the reactions between ideas.

The assumption is that if you’re sitting down to write a story, you have at least one of these tent poles already. Chris had the first glimpse of a setting: a place for adventurers to both meet and adventure.

Let’s play with the model for a second with an idea of our own.

The setting is an attic. Alright, let’s go to emotion/atmosphere: Is there a sense of dread or mischief or discovery? Discovery, yes that feels right. Alright, so that conjures more of the setting for me: a tome of magic buried at the bottom of Grandpa’s old WWII locker. Who found it (character)? Francis. Well, who’s Francis….I don’t know yet. I need another question.

Why was she up in the attic (situation)? Hiding. She’s young, and avoiding someone. Who is she avoiding? No, I don’t like that path – she’s bored and curious, and has snuck off from her Grandparents to explore.

And you can keep going.

Maybe answers change as you go (tome of magic isn’t quite precise enough, some relic that Grandpa brought back from the war…am I sensing something like Hellboy? Oh…maybe Klosterheim! That’s interesting…).

Alright, alright the point is you get the creative clay wet and start making shapes, giving definition.

And if you’re full up on inspiration and influence, then there are plenty of elements and patterns buried deep in the subterranean depths of your subconscious that can come to life in that clay.

Good, good. But let’s dialogue some more.

Not Quite Zettelkasten

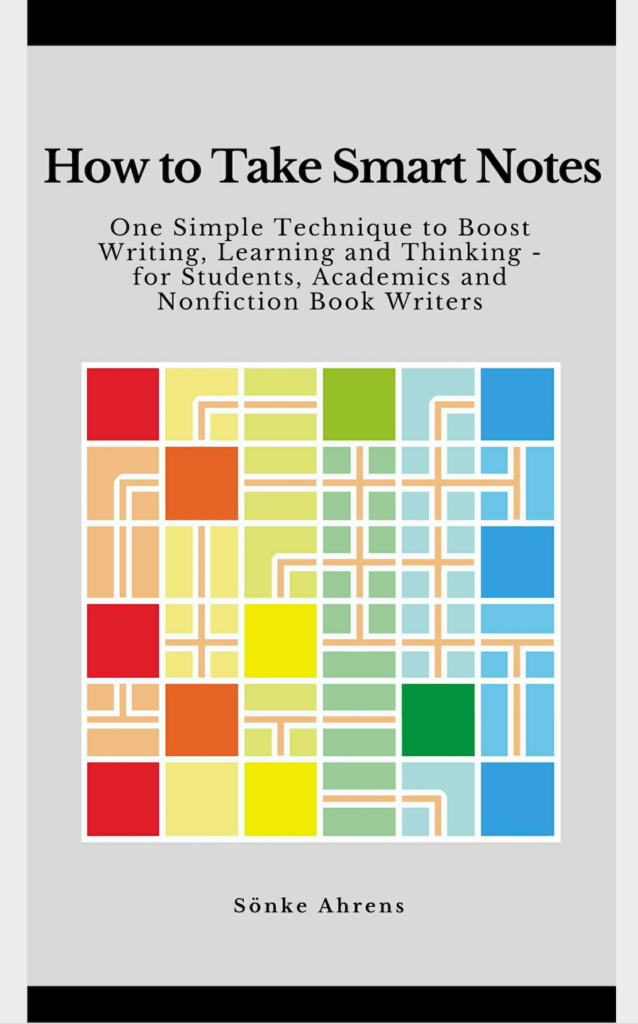

The method of Zettelkasten (slip-box) has enjoyed a lot of renewed attention of late. It is essentially a tool for note making and knowledge management that encourages discovering fruitful relationships between ideas. Thus there is potential value in examining it for the purposes of creative dialoguing with our story/world ideas.

The sociologist Niklas Luhmann created a system of some 90,000 index cards in shoeboxes that became the idea generator for a quiet prolific career.

The generator is powered not by notes taken but notes made. Note taking is more akin to marginal notations in a text or quotes scribbled down somewhere – the reader doesn’t own the ideas, he’s just copying or highlighting them. Note making is about recording our best thinking on an idea as we respond to our reading. This best thinking grows on a notecard, becoming an anchor point of distilled understanding that we can bring into reactive contact with other ideas.

In time we reach a critical mass (something like what Chris Pramas enjoys as a veteran game designer), and creative stuff happens.

It’s quite the potent non-fiction research writing tool and it has application for fiction projects as well (though you have to make adjustments). There are computer programs that claim to duplicate the power of the system in the digital space, such as Obsidian (which I use as a tool in my process), but the shoebox/analog method is quite powerful.

My go-to text for learning about and developing Zettelkasten-adjacent systems is How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens. Here is something of his thinking:

Working with the slip-box means playing with ideas and looking out for interesting connections and comparisons. It means building clusters, combining them with other clusters and preparing the order of notes for a project. Here, we need to puzzle with notes and find the best fit.

This may be one of the most important sections of Ahrens’ book to dwell upon. The slip-box becomes the sandbox where we play with ideas, building out clusters that interact with one another. It’s a creative locus of associative puzzling – a playground of creative dialogue.

Here is a promising way to address knots in the creative process of generating a story. If the core ideas can be isolated and understood so as to be played with like a chemistry experiment (more “reaction” language), then story ideas can be resolved into exciting solutions and the story can potentially write itself as the reactions occur (recall the If-Then inevitability that I spoke of when observing Pramas’ account of creating Death in Freeport).

So far our conversation has taken us into families and groups of ideas. But there are also ideas that are so large that they overshadow all the rest…

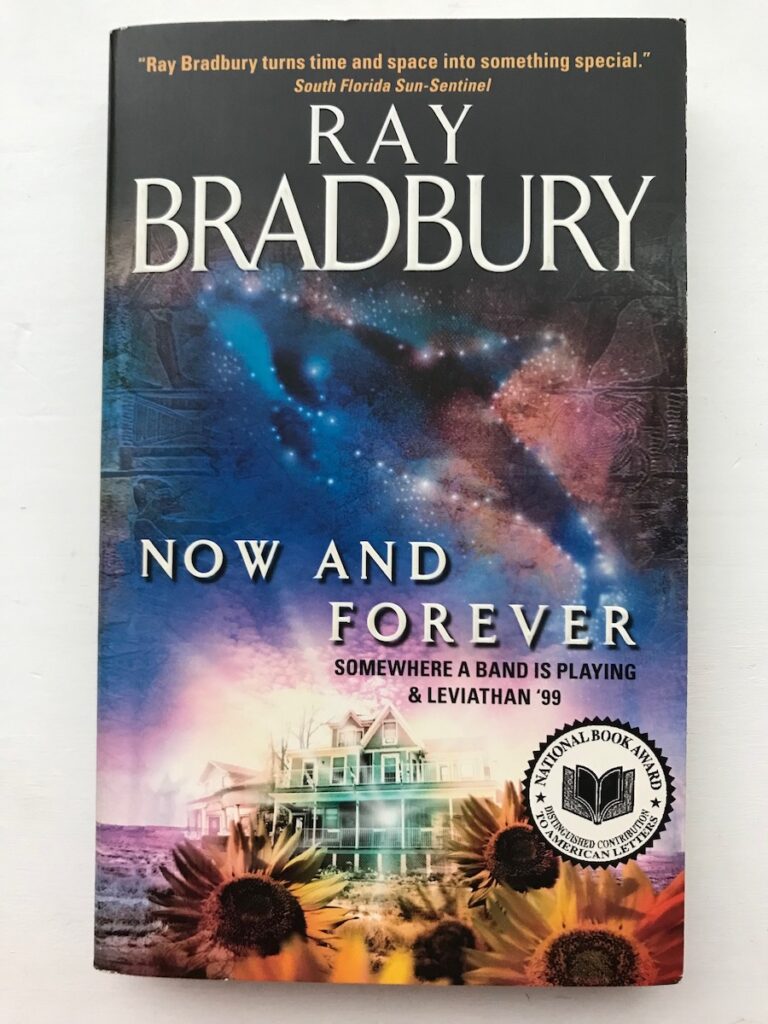

When Leviathan Looms

Capture the big metaphor first; all the rest will rise to follow. Don’t bother with the sardines when the leviathan looms. He will suction them in by the billions once he is yours.

Ray Bradbury, “The Whale, the Whim, and I,” in Bradbury Speaks: Too Soon From the Cave, Too Far from the Stars

Some ideas are so big, so powerful that they reconfigure all other ideas around themselves. Bradbury encouraged writers to keep their eyes out for these “leviathans,” the central images and metaphors that define the DNA of stories.

You can see this kind of thinking at work in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (that’s what Bradbury is referring to by the way – he was inspired by the White Whale a lot himself). Melville is clearly captured by his subject as you read along. Just consider all the effort he went into compiling every reference he could on whales at the front of the book – there are eighty of them, by the way.

Roger Zelazny, in his essay “An Exorcism of Sorts” gets at this big idea thinking, only he outlines his concept in three categories: the striking image, character, or idea that comes in and demands to be written. These are his “three doorways into fiction.” His comments on characters in particular are not so dissimilar from what happened with Robert E. Howard and Conan that I wrote about elsewhere:

With some of my stories a character such a Dilvish, Kalifriki, Mari, or Conrad comes in out of the night, takes my attention hostage and waits. Circumstances then suggest, events coalesce, and the story flows like a shadow. Generally, tales such as this are longer pieces; novels, even. Once I’ve seen their shapes, they exist as ghosts for me till I’ve pinned them to paper.

Roger Zelazny, “An Exorcism of Sorts,” Frost & Fire

This kind of “dominating idea” (as Mikhail Bakhtin called it) can also be found at work in the writing of Dostoevsky, here’s Bakhtin:

A “dominating idea” was mentioned in the plan of every one of Dostoevsky’s novels. In his letters he often emphasized the extraordinary importance he attached to the basic idea.

Mikahil Bakhtin, “The Idea in Dostoevsky,” Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, 99

For example, in The Idiot, the author was captured by the idea of writing a story centered around a “positively good and beautiful man.” Though he didn’t believe he was fully successful, he was able to say: “I do stand behind the idea.”

Or consider The Possessed (sometimes also translated Demons in English), Dostoevsky wrote: “The idea seduced me and I’ve fallen terribly in love with it, but can I manage it without ruining the whole novel – that’s the trouble!”

Indeed, that is the promise and the peril of immensely powerful ideas: they can be the cores of stunning stories or they can ruin a tale entirely if not properly managed.

Dialoguing As Creative Chemistry

If ideas are the fundamental elements of stories (and worldbuilding), then all we need is one idea to get started creating. From there we can play: interrogate, explore, accumulating from the inside out, framing and filling from the outside in, colliding idea with idea, bouncing them around a matrix of four tent poles (or more) – whatever it takes to keep the dialogue going.

We can even just fill up our shoebox with research and concepts, or let ideas marinate in our subconscious until something reaches critical mass.

And sometimes – maybe even often – leviathan may loom up into our creative view, and if we should lay hold of him, he will drag our imagination into new, unexpected, and glorious waters.

Want more words? See the horse below about a newsletter. Or scroll on down to make a comment.