Worldbuilding in fantasy (and science fiction) is often described as the creation of an apparatus of notes and documents organized by topic: cultures, geography, magic, and so forth.

What all the topics in this approach hold in common is that they are created from the perspective of our own world – as if the author were documenting observations at an archaeological dig site using the language of analogy.

One might make note of a “Viking-esque” culture, a river “like” the Amazon, mountains “like” the Hindu Kush, poetry and historical periods, even how day and night work – they all show up on the drafting table alongside the actual prose of a story, anchored by reference to our world.

There is a certain sense to this approach: Our world is – inescapably – our primary reference, so this kind of creative-analogy shorthand points us to the broader wealth of our own understanding about, say, Vikings or the Amazon.

Indeed, this model grants us ready access to storehouses of material to work from when we build our world:

The term “Viking-esque culture” carries inside it the substance of heroes, inventions, discoveries, wars, myths, stories, language – as much as the author can learn about Vikings really.

Parody, Novelty, and Composition

Of course, we risk parody if we make things too close to our own world, but authors like Guy Gavriel Kay have made brilliant careers elegantly modeling their worldbuilding on our own. (And Robert E. Howard had plenty of fun mashing things together.)

Yet a further advantage for the worldbuilder is that the things referenced need not even be “real.”

If I say, “Dragon,” that draws upon significant, pre-established imaginative capital – a deep well. Indeed, the word “Dragon” has accumulated an impressive weight of reference (not all of it useful) around it: East and West, reaching back millennium from the present day.

It is impossible to fully escape this connection to our world – whatever the demands of such forces as the Cult of Novelty (as Solzhenitsyn called it). Even authors like Brandon Sanderson, who have sought to build alien fantasy worlds, still write in an earth language and make references to earthly things.

One can make the argument that nothing that we humans make is truly unique – or sui generis – simply because everything we make is composed from materials that pre-existed our discovery of them.

We don’t create anything ex nihilo – out of nothing. Instead we weave unique compositions out of the givenness of things.

This is a concept a certain professor gave plenty of thought to…

Sub-creators of Secondary Worlds

Tolkien presented the concept of humans as Sub-creators of secondary worlds in both his poem “Mythopoeia” and his essay “On Fairy Stories.” And he defined our creative role as bound up with our essential identity:

Though all the crannies of the world we filled

– from Mythopoeia, by Tolkien

with elves and goblins, though we dared to build

gods and their houses out of dark and light,

and sow the seed of dragons, ’twas our right

(used or misused). The right has not decayed.

We make still by the law in which we’re made.

This theory of sub-creation is an argument for both the practice and purpose of the fantasy author: the practice being to fashion imaginings into works of substance and the purpose being the enrichment and adornment of our primary world.

What is interesting is how Tolkien went about living out this “law in which we’re made.” He invested much of his effort and vision into creating stories that would constitute a unified body of mythology.

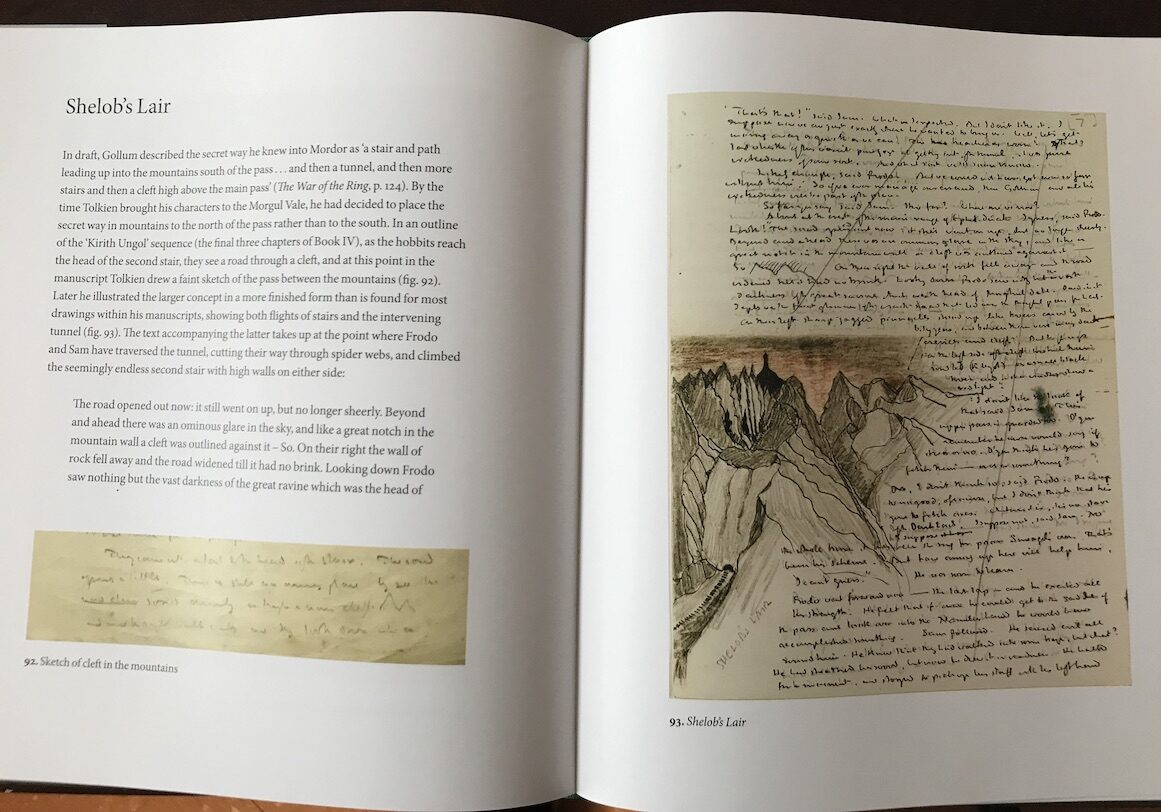

Before The Lord of the Rings was even an idea, Tolkien already had a well-cultivated trove of stories. And these stories went through a variety of forms, changing as the years went on and Tolkien’s vision matured. (Also he had, at least, two other advantages: He could write in Elvish and he was an artist!)

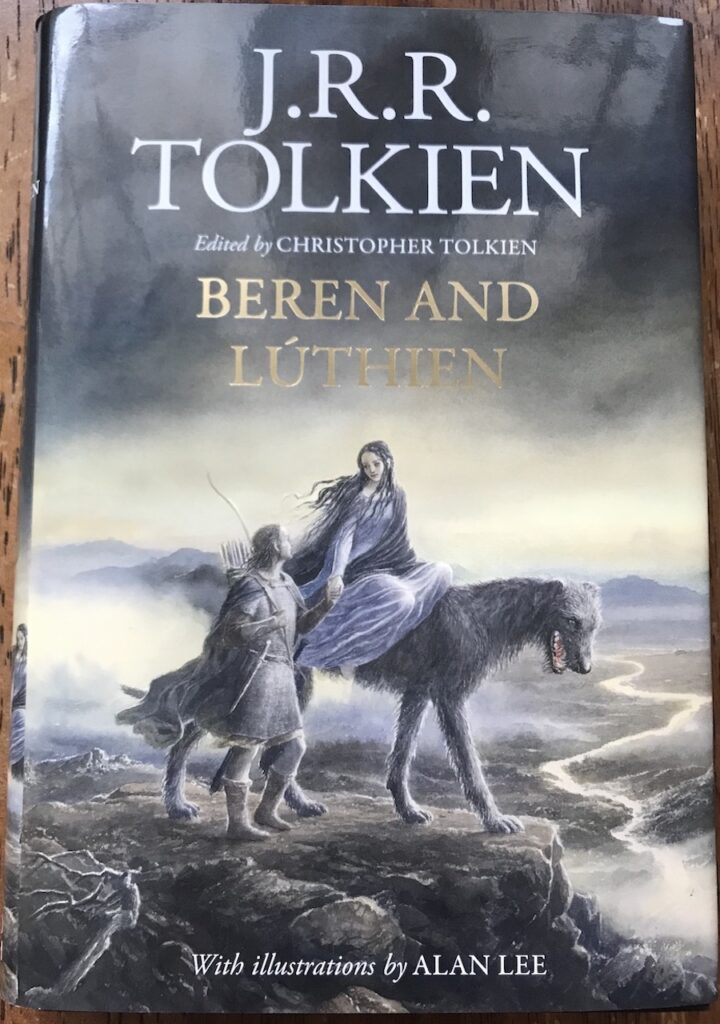

Tevildo the Prince of Cats became the Necromancer Thû, the Lord of Werewolves, who in turn became Sauron – a straightforward example of how one character changed over time.

Tolkien wasn’t actively seeking to build a mythology to enrich The Lord of the Rings, indeed, the world of the hobbits was separate from the mythology for some time (even though there were glimmers of it in The Hobbit).

So, we can safely say he wasn’t intentionally worldbuilding for a larger work – but he was creating a corpus of stories that could ultimately be referenced, alluded to, distorted, misremembered, and held on to for encouragement within the narrative frame of Middle Earth.

A Brief Comparison in Technique

Consider a comparison in create-as-you-go approaches:

In Star Wars: A New Hope, we have a tantalizing exchange between Obi-Wan and Luke in which we receive a quick series of worldbuilding gestures: Jedi Knight, space freighter pilot, Clone Wars.

This is gestural world building through storytelling, and it works quite well.

Fans of Lucas’ work were talking about these tantalizing hints for decades before they were more fully explored. Plenty of writers (particularly those of the discovery writing school) go about worldbuilding in this way – and find great success.

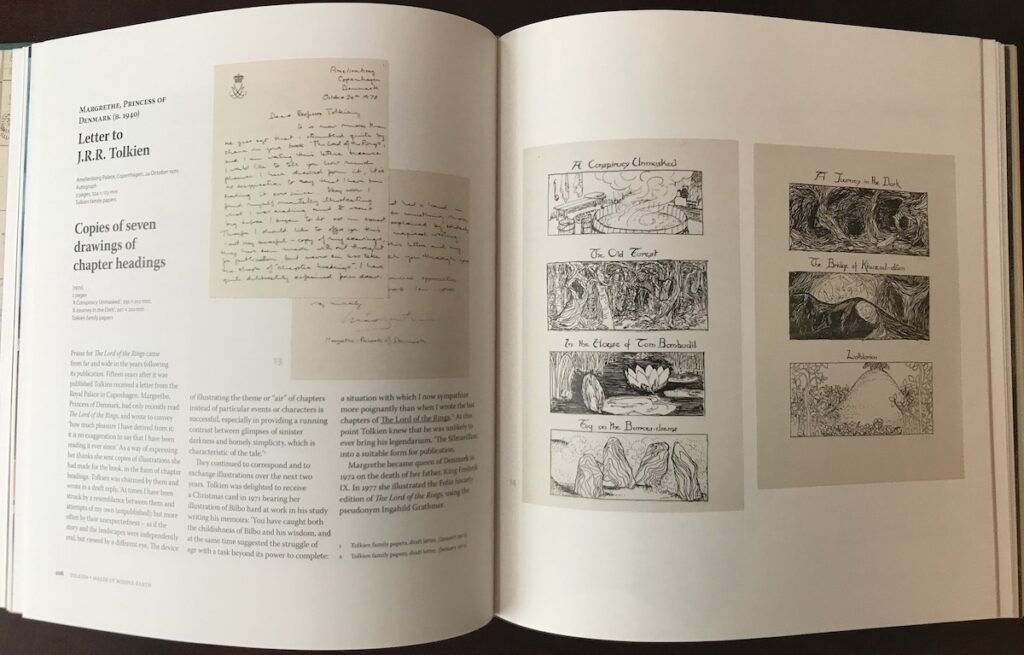

Now, let’s take the “Song of Eärendil” recited by Bilbo in Rivendell. This, the longest poem in LotR, wasn’t written to fill up space in the book or because Tolkien wanted to show what a great poet Bilbo was – it had been written long ago, even before The Hobbit.

The song itself in The Fellowship of the Ring ends with Eärendil ascending from the blessed land of the west to become a star by the power of the Silmaril bound to his forehead.

Yet, in the Legendarium, his arrival in the blessed land provokes the powers that dwell there to at last rouse themselves and bring war against Morgoth, The Great Enemy of whom Sauron is but a servant. It is the end of the First Age, just as Frodo’s victory will mark the end of the Third.

That alone would be a deft and subtle act of worldbuilding. But, Tolkien doesn’t stop there.

Story within Story within Story

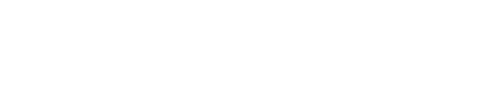

Galadriel gives Frodo a glass with the light of Eärendil in it – light from the Silmaril, which itself was forged from the light of the trees at the dawn of creation, trees that were slain by Ungoliant the Primordial Spider of Darkness, Mother of Shelob. Shelob, whom Frodo and Sam will confront with the light of the glass later in The Two Towers.

Thus, for the elves, Frodo is typologically in the tradition of Eärendil, so it isn’t a surprise that he is given a place on a grey ship and allowed to come to the blessed land at the end of the story.

Now, the reader doesn’t need any of that information to enjoy the confrontation with Shelob, but the reward is there to be had.

(See also the references to Frodo as Elf-friend in Fellowship, beginning with Gildor Inglorion in “Three is Company,” re-asserted by Goldberry “In the House of Tom Bombadil,” and expanded upon by Elrond at the Council – placing Frodo in the tradition of the “mighty” ones “Hador, and Húrin, and Túrin, and Beren.”)

These are intertextual echos that bind the whole work together, enriching it with depth and texture. Tolkien interweaves his secondary creations with each other, worldbuilding through nesting stories.

One could say that Tolkien’s advantage while writing LotR was he didn’t just have reference to the primary world that you and I live in – his secondary world had dimensionality and depth all its own to draw upon.

He already had poetry, themes, history, old conflicts, geography, and more to bring to his canvas. All because he was a having a grand time playing at creating – language, art, poetry, stories.

A Worldbuilding Model to Emulate

Tolkien’s approach of creating a mythology that became the foundation of his worldbuilding process is a powerful creative model, especially for fantasists looking to craft an epic or a body of works in the same world.

Consider: Instead of reaching a point in the creative process and saying, “Oh, I need a creation myth here,” or “Wouldn’t an allusive story hinting at an ancient evil be great to throw into the mix,” you already have sketches of your creation myth(s) and a rich understanding of certain ancient powers that might be skulking about.

Now, I’m not advocating writing an entire mythology (The Silmarillion – and the writings associated with it – isn’t everyone’s cup of tea and you don’t have to write one to write great fantasy.)

But, when approaching worldbuilding, what if the creative methodology included secondary creations?

Here a map drawn by a cartographer from your world, there a couple of pages from the journal of the founder of this city, this poem was written to immortalize a great battle, this law code is central to a culture.

Follow the interest and the insight.

You may discover that the creation of proverbs attributed to a god gives you unique insight into how a people view the world. If you go on making them, you’ll have a word-hoard of wisdom to draw upon at unexpected moments.

More Time Building What You Love

Worldbuilding through creating in the world makes for richer, more dynamic creations. The product is far more interesting than notes that can often feel cold and disconnected from the work itself (not to say I’m against notes – I’ve made plenty of them and I’m actually fascinated by the concept of adapting a method like Zettelkasten to grow a story).

There’s also the added advantage that you don’t have to resolve all the differences between different sub-created elements: the stories can disagree, the maps can be different, the details don’t have to match. (Well – at least as long as you’re not a monologic author.)

That makes for a lot of fun. It’s also more time spent in the world you’re making for your readers.

And isn’t that what most of us want when we’re writing what we love?

Want more words? See the horse below about a newsletter. Or scroll on down to make a comment.